Archiv

NSA Dokumente: Henry Kissinger Morde, Folter in der Welt

Mord, Terroristen Finanzierung wie in Syrien, Deutschland war bei jeden Verbrechen der Amerikaner dabei bis heute und Nazis als Partner, waren von Kroatien. Kosovo besonders Willkommen, wie man an der Ukraine sieht bis Litauen, Georgien

Die Massen Morde der Amerikaner mit Suharto in Indonesien

Oktober 7, 2010

2016

Henry Kissinger’s Documented Legacy

Henry Kissinger, 1975 (Wikimedia Commons)

A Declassified Dossier on HAK’s Controversial Historical Legacy, on His 100th Birthday

Archive Posts Revealing Records of Kissinger’s Role in Secret Bombing Campaigns in Cambodia, Illegal Domestic Spying, Support for Dictators and Dirty Wars Abroad

Published: May 25, 2023

Briefing Book #

829

Edited by Peter Kornbluh and

William Burr

For more information,

contact Peter Kornbluh:

202-994-7000 or peter.kornbluh@gmail.com

Events

Argentine Dirty War, 1976-1983

Project

The Kissinger Transcripts: The Top-Secret Talks with Beijing and Moscow

Feb 1, 1999

Pinochet Desclasificado:

Los Archivos Secretos del Los Estados Unidos Sobre Chile

(Catalonia Press: June 2023)

The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability

Sep 11, 2013

Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations between Washington and Havana

Oct 13, 2014

Washington D.C., May 25, 2023 – As Henry Alfred Kissinger (HAK) reaches 100 years of age on May 27, his centennial is generating global coverage of his legacy as a leading statesman, master diplomat, and realpolitik foreign policy strategist. “Nobody alive has more experience of international affairs,” as The Economist recently put it in a predictably laudatory tribute to Kissinger. During his tenure in government as national security advisor and secretary of state (January 1969 to January 1977), Kissinger generated a long paper trail of secret documents recording his policy deliberations, conversations, and directives on many initiatives for which he became famous—détente with the USSR, the opening to China, and Middle East shuttle diplomacy, among them.

But the historical record also documents the darker side of Kissinger’s controversial tenure in power: his role in the overthrow of democracy and the rise of dictatorship in Chile; disdain for human rights and support for dirty, and even genocidal, wars abroad; secret bombing campaigns in Southeast Asia; and involvement in the Nixon administration’s criminal abuses, among them the secret wiretaps of his own top aides.

To contribute to a balanced and more comprehensive evaluation of Kissinger’s legacy, the National Security Archive has compiled a small, select dossier of declassified records—memos, memcons, and “telcons” that Kissinger wrote, said and/or read—documenting TOP SECRET deliberations, operations and policies during Kissinger’s time in the White House and Department of State. The revealing “telcons”—over 30,000 pages of daily transcripts of Kissinger’s phone conversations many of which he secretly recorded—were taken by Kissinger as “personal papers” when he left office in 1977 and used, selectively, to write his best-selling memoirs. The National Security Archive forced the U.S. government to recover these official records by preparing a lawsuit that argued that both the State Department and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) had inappropriately allowed classified U.S. government documentation to be removed from their control; once they were returned, Archive senior analyst William Burr filed a FOIA request for their declassification. The draft lawsuit—which was never filed—is included in this dossier, since Kissinger’s effort to remove, retain and control these highly informative and revealing historical records should be considered a critical part of his official legacy.

This special posting also centralizes links to dozens of previously published collections of documents related to Kissinger’s tenure in government that the Archive, led by the intrepid efforts of William Burr, has identified, pursued, obtained and catalogued over several decades. Together, these collections constitute an accessible, major repository of records on one of the most consequential U.S. foreign policy makers of the 20th century.

I. KISSINGER, THE SECRET BOMBINGS AND WIRETAPS

In the fall of 1968, then Harvard professor Henry Kissinger used his access as an advisor to the State Department to become a secret informant to the Nixon campaign on the Johnson Administration’s peace talks in Vietnam. If LBJ succeeded in ending the war, Nixon feared losing the election to Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Secretly, Nixon pressed the South Vietnamese government to jettison the talks, promising them a better deal once he was elected.

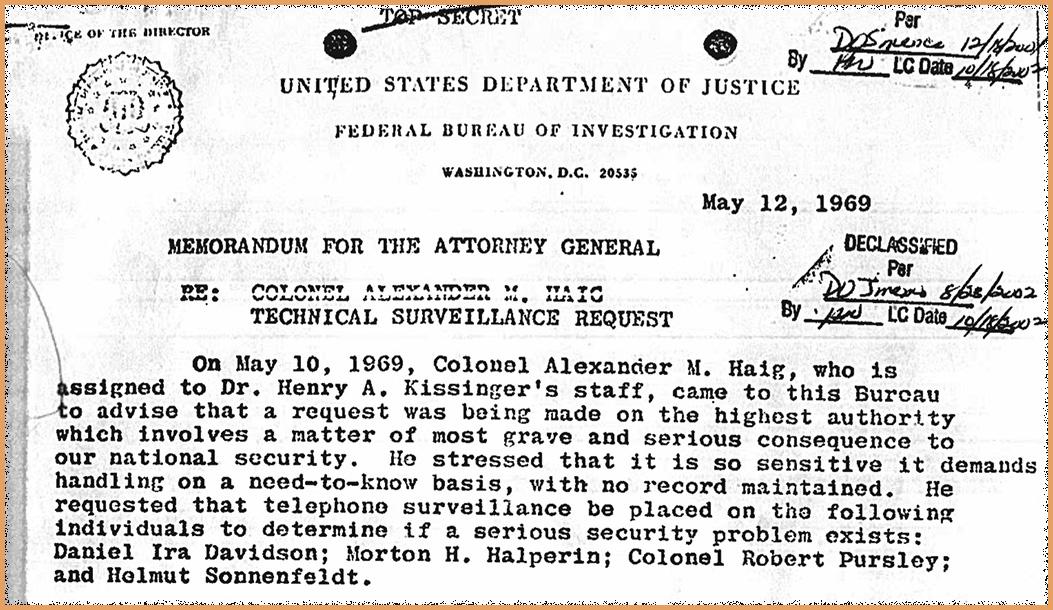

Within weeks of Nixon’s inauguration, he decided with his new national security advisor that secretly bombing North Vietnamese supply routes in Cambodia and Laos was one way to force Ho Chi Minh back to the negotiating table on U.S. terms. The bombing raids, codenamed “Breakfast Plan” and “Operation Menu,” began on March 17, 1969, and lasted over a year, killing thousands of Cambodian noncombatants. After the New York Times ran its first story on May 9, 1969, exposing the covert B-52 bombing program, Kissinger asked FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to wiretap specific journalists and U.S. officials, including his own aides at the NSC, to identify who was leaking information to the media. The first of his aides to be placed under surveillance, an NSC staffer named Morton Halperin, resigned and eventually sued Kissinger, Nixon and the Justice Department for illegally wiretapping his office and home phones.

When the wiretap scandal broke, Kissinger stated that his role was limited to supplying an initial set of names to the FBI; when he was deposed in the Halperin lawsuit, however, he claimed that Hoover had identified those individuals. Kissinger’s deputy, Alexander Haig, who transmitted the names of suspected leakers to the FBI for a period of two years, said that Kissinger provided him with those names. According to Halperin’s lawsuit, on the day of the first New York Times story, “Hoover and Kissinger conferred by telephone four times that day, and the wiretap on the Halperin home telephone was in place by evening.”

Hoover sent wiretap surveillance reports on Halperin and other targets directly to President Nixon. One of those reports was recently declassified by the Nixon library and is included in this posting. “The illegal and rule-less government wiretaps not only violated the right to privacy but interfered with the political rights of those surveilled and those they talked to,” Halperin noted in a statement to the Archive for this posting. ”These surveillance records remind us of the need for eternal vigilance and accountability.”

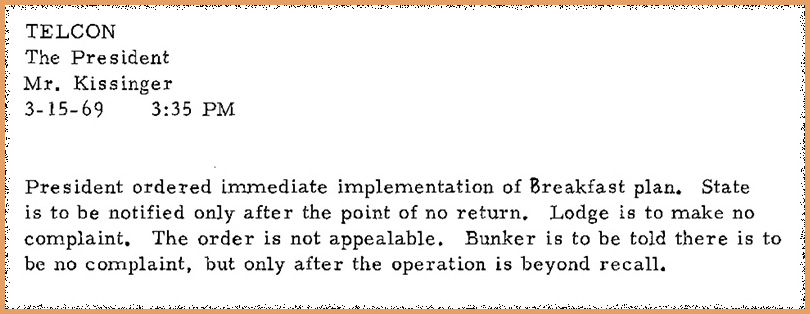

Document 1.1

Mar 15, 1969

Source

Digital National Security Archive (DNSA), The Kissinger Telephone Conversations: A Verbatim Record of U.S. Diplomacy, 1969-1977.

After receiving an order from President Nixon at 3:35pm on March 15, 1969, for “immediate implementation of Breakfast plan,” Kissinger transmits Nixon’s decision to begin the secret bombing of Cambodia, to the Secretary of Defense. “K said to lay on above for Monday afternoon our time, Tuesday morning their time. L said he would,” according to the summary. Kissinger warns Laird that “there is to be no public comment at all from anyone at any level, either complaining or threatening.” This is intended to be a TOP SECRET operation.

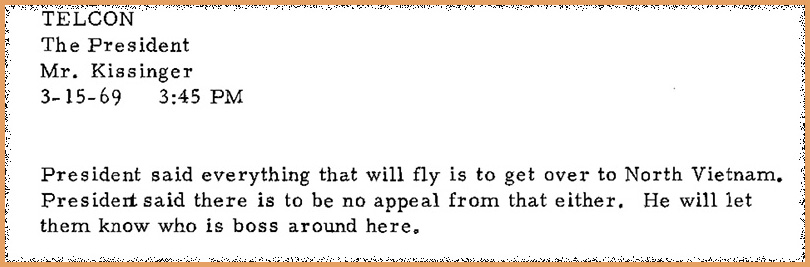

Document 1.2

Mar 17, 1969

Source

DNSA, The Kissinger Telephone Conversations: A Verbatim Record of U.S. Diplomacy, 1969-1977.

Only hours before the first secret aerial bombing of Cambodia, Kissinger briefs Nixon on preparations. “K said it is all in order,” according to the summary of their phone conversation. The two comment on how South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu has already agreed to private talks.

Document 1.3

Mar 18, 1969

Source

DNSA, The Kissinger Telephone Conversations: A Verbatim Record of U.S. Diplomacy, 1969-1977.

Kissinger gets a short briefing from Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Earle Wheeler on the success of the initial bombing raids. He advises the military to undertake additional “hits.” “HAK said they should put in 2 or 3 more hits along the whole area if we get the right intelligence.” Kissinger also shares his assessment of the impact of the sudden, secret raids: “Psychologically, the impact must have been something,” he states. In response, General Wheeler suggests the shock of the bombing will force the North Vietnamese back to the Paris peace talks: “Wheeler said they probably already had their speech written for Paris.”

Document 1.4

NSC, Telcon, Kissinger and President Richard M. Nixon, December 9, 1970, 8:45 p.m.

Dec 9, 1970

Source

DNSA, Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversations Transcripts, Home File, Box 29, File 2

In the wake of a year of secret bombing raids, President Nixon remains anxious about the Cambodian situation. In this telephone call, Nixon orders Kissinger to direct bombing attacks on North Vietnamese forces there ”tomorrow.” He wanted to ”hit everything there,” using the ”big planes” and the ”small planes.” ”I don’t want any screwing around,” Nixon says.

Document 1.5

White House, Telcon, Kissinger and General Alexander M. Haig, Jr., December 9, 1970, 8:50 p.m.

Dec 9, 1970

Source

DNSA, Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversations Transcripts, Home File, Box 29, File 2, 106-10

A few minutes after receiving Nixon’s call on Cambodia, Kissinger telephones his military assistant, Alexander Haig, about the orders from ”our friend.” After he describes Nixon’s instructions for a ”massive bombing campaign” involving ”anything that flys [sic] on anything that moves,” the notetaker apparently heard Haig ”laughing.” Both Haig and Kissinger knew that what Nixon had ordered was logistically and politically impossible so they translated it into a plan for massive bombing in a particular district (not identifiable because the text is incomplete). These two phone calls illustrate an important feature of the Nixon-Kissinger relationship: while Nixon would, from time to time, make preposterous suggestions (no doubt depending on his mood), Kissinger would later decide whether there was a rational kernel in what Nixon had said and whether, and/or how, to follow up.

Document 1.6

May 12, 1969

Source

Elliot Richardson Papers, LIbrary of Congress.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover transmits a TOP SECRET report to Attorney General John Mitchell on Kissinger’s request for telephone surveillance on four U.S. officials “to determine if a serious security problem exists.” According to the memo, the names have been brought to the FBI by Kissinger’s military deputy, Col Alexander Haig, who states that the matter is “of most grave and serious consequence to our national security.” Nixon and Kissinger had directed the FBI to begin a leak investigation and wiretaps almost immediately after the New York Times broke the story on the secret bombing raids over Cambodia.

Document 1.7

FBI, J. Edgar Hoover Wiretap Surveillance Report to President Nixon, TOP SECRET May 11, 1970

May 11, 1970

Source

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Mandatory Declassification Review Request

In one of a series of reports to President Nixon on individuals targeted for wiretap surveillance by Kissinger’s office, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover shares information on three individuals: London Sunday Times reporter Harry Brandon; Kissinger’s former aide Morton Halperin, and State Department official William Sullivan, who is overheard speaking to former ambassador W. Averell Harriman. The wiretaps capture innocuous conversations by Brandon’s wife about opposition to Kissinger’s Vietnam policies among his former Harvard colleagues, and Halperin’s plans to quietly resign from the White House staff where he has been a part time consultant since stepping down as a top specialist on Kissinger’s NSC. The wiretap on Sullivan produces information that Ambassador Harriman plans to host a gathering at his home of State Department officials who had signed a letter of protest against the secret bombing of Cambodia. The FBI subsequently uses this information to physically surveil the meeting at Harriman’s house—a fact that emerges in congressional hearings on the wiretap scandal four years later.

Document 1.8

White House, Telcon, “The President/Mr. Kissinger 7:00pm., June 1, 1973 [Discussing wiretap scandal]

Jun 1, 1973

Source

DNSA, Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversations

After the wiretap scandal breaks into the media, Nixon orders a report on wiretapping under previous administrations. He calls Kissinger in anger to tell him: “Let’s get away from the bullshit. Bobby Kennedy was the greatest tapper.” He accuses the former attorney general of tapping the phones of 300 people in 1963 and tells Kissinger that he is going to publish the names of those individuals Kennedy had placed under surveillance. “And let the[se] assholes know that they’re going to get this, Henry.” Kissinger responds: “I think you should.” “They started it,” Nixon reiterates. “They want to have a g[ood] fight; they’re going to get one, Henry, you understand.”

Document 1.9

Mar 13, 1976

Source

DNSA, Nixon Presidential Materials Project, Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversations

In one of a number of conversations with Attorney General Edward Levi, Kissinger complains about how the Justice Department is handling the Halperin suit against him. Halperin’s lawyers are telling the press that there are “inconsistencies” between his story and other testimony in the case [likely witnesses such as Alexander Haig stating that Kissinger provided the names for the FBI of individuals to be put under surveillance as potential leakers.] Kissinger complains that the lawsuit is undermining his ability to do his job. “Right now the Secretary of State is being accused of lying, perjury, [and] conflicts are being printed in newspapers,” he tells the Attorney General. “I had a senior official of the Russian Embassy ask me whether my effectiveness was being damaged the other day.” Kissinger adds: “My philosophy is when in doubt attack.”

Chile’s ruler Augusto Pinochet meeting U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Santiago, June 8, 1976 (Wikimedia Commons)

Chile’s ruler Augusto Pinochet meeting U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Santiago, June 8, 1976 (Wikimedia Commons)

II. KISSINGER AND CHILE

Chile is arguably the Achilles heel of Kissinger’s legacy. The declassified historical record leaves no doubt that HAK was the chief architect of U.S. efforts to destabilize the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. In the weeks before Allende was inaugurated, CIA documents reveal, Kissinger supervised covert operations—codenamed FUBELT—to foment a military coup that led directly to the assassination of Chile’s commander-in-chief of the Army, General René Schneider. After initial coup plotting failed, Kissinger personally convinced Nixon to reject the State Department’s position that Washington could establish a modus vivendi with Allende, and to authorize clandestine intervention to “intensify Allende’s problems so that at a minimum he may fail or be forced to limit his aims, and at a maximum might create conditions in which collapse or overthrow might be feasible,” as Kissinger’s talking points called for him to tell the National Security Council, three days after Allende’s inauguration. The U.S. “created the conditions as great as possible,” Kissinger informed Nixon only days after Allende was overthrown 50 years ago on September 11, 1973. “[I]n the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes,” he added.

Kissinger designed U.S. policy to keep Allende from consolidating his elected government; but once General Augusto Pinochet’s forces violently took power, the documents demonstrate, Kissinger reconfigured U.S. policy to assist the consolidation of a brutal military dictatorship. “I think we should understand our policy—that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was,” he told his deputies as they reported to him on the human rights atrocities in the weeks following the coup. At a private June 1976 meeting with Pinochet in Santiago, Kissinger told the Chilean dictator: “My evaluation is that you are a victim of all left-wing groups around the world and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government which was going communist.”

“We want to help, not undermine you,” Kissinger informed the General, disregarding advice from his own ambassador to give Pinochet a direct, tough message on human rights. “You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”

Document 2.1

Sep 12, 1970

Source

DNSA

Only days after Salvador Allende’s election, Kissinger speaks to Secretary of State William Rogers about plans to block his inauguration. Rogers reluctantly agrees that the CIA should “encourage a different result” in Chile but warns it should be done discreetly lest U.S. intervention against a democratically elected government be exposed. Kissinger firmly tells Rogers that “the president’s view is to do the maximum possible to prevent an Allende takeover, but through Chilean sources and with a low posture.” (Note: this page of the telcon has been misdated as September 14; page 1 makes it clear that the conversation took place on September 12, 1970.)

Document 2.2

NSC, Memorandum, “Chile—40 Committee Meeting, Monday – September 14,” SECRET, September 14, 1970

Sep 14, 1970

Source

Clinton Administration Chile Declassification Project

In a memorandum to prepare Henry Kissinger for a 40 Committee meeting on covert options to block Allende’s inauguration in Chile, his top deputy for Latin America, Viron Vaky, takes the opportunity to warn against U.S. efforts to block Allende. In addition to the costs of possible exposure to the reputation of the United States abroad, he advances a bold moral argument: “What we propose is patently a violation of our own principles and policy tenets.” Over the coming days, weeks, and months, Kissinger will chair the 40 Committee meetings determining and overseeing covert operations to undermine Allende’s presidency.

Document 2.3

Sep 15, 1970

Source

Senate Select Committee to Study Government Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, Covert Action in Chile, 1963-1973.

On September 15, 1970, Kissinger participates in a fifteen-minute Oval Office meeting with President Nixon and CIA director Richard Helms on Chile. Notes taken by the CIA director record Nixon’s orders to the CIA to “make the economy scream” and to prevent Allende from being inaugurated as president of Chile. Nixon directs Helms to put together a “game plan” in 48 hours, which is then shared with Kissinger who becomes the de facto supervisor of the initial CIA efforts to foment a military coup before the inauguration in early November.

Document 2.4

Oct 15, 1970

Source

Senate Select Committee to Study Government Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, Covert Action in Chile, 1963-1973.

This memorandum of conversation summarizes a meeting between Henry Kissinger, his deputy, Alexander Haig, and the CIA’s Thomas Karamessines to evaluate the status of coup plotting in Chile. The key plotter who is receiving CIA support, retired General Roberto Viaux, “did not have more than one chance in twenty-perhaps less-to launch a successful coup,” Karamessines reports. After Kissinger lists the negative consequences of a failed coup, they decide to send a message to Viaux warning him not to take precipitate action and advising him that “The time will come when you with all your other friends can do something. You will continue to have our support.“ Dr. Kissinger instructs Karamessines that the CIA “should continue keeping the pressure on every Allende weak spot in sight—now, after the 24th of October, after 5 November and into the future…” A CIA report cabled to Santiago immediately following the Kissinger meeting states that “it is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup.”

Document 2.5

Nov 12, 2002

Source

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

The covert CIA operation that Kissinger supervised to foment a coup before Allende’s inauguration led directly to the assassination of the pro-Constitution Chilean commander-in-chief of the Army, General Rene Schneider. On September 10, 2001, the sons of General Schneider, Raul and Rene Schneider, filed a civil lawsuit against Henry Kissinger and the U.S. government for the “wrongful death“ of their father. This complaint, as amended in November 2002, cited the declassified U.S. record as evidence of liability in the case. According to the petition: “Recently declassified U.S. government documents and congressional reports have provided Plaintiffs with the information necessary to bring this action. The documents show that the knowing practical assistance and encouragement provided by the United States and the official ultra vires acts of Henry Kissinger resulted in General Schneider’s summary execution, torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detention, assault and battery, negligence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and wrongful death.” The civil lawsuit was eventually dismissed because the judges ruled that Kissinger had immunity for actions he took as part of his official responsibilities as national security advisor to the President.

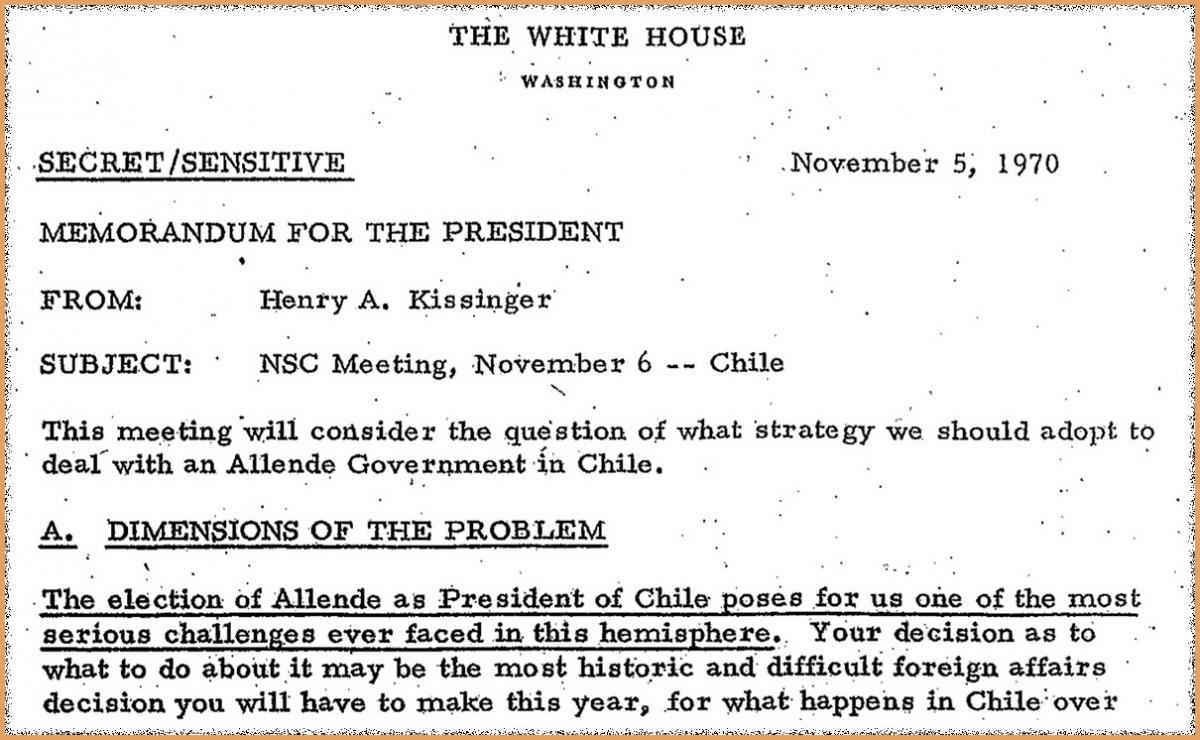

Document 2.6

Nov 5, 1970

Source

Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability (The New Press, 2013) pp. 121-128.

After the failure of the CIA to foment a coup to prevent Allende’s inauguration, the Nixon White House scheduled an NSC meeting on November 5 to determine US policy toward an Allende government. But Kissinger asks that the meeting be postponed a day to November 6, in order to lobby Nixon to reject the State Department’s position that Washington foster a modus vivendi with Allende. Instead, Kissinger argues, Nixon should „make a decision that we will oppose Allende as strongly as we can and do all we can to keep him from consolidating power,” as he writes in this pivotal memorandum, explaining why the first freely elected Marxist government in the world must not be allowed to succeed. “The election of Allende as President of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere,” Kissinger submits in his opening sentence, underlining it for effect. “Your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will have to make this year,” he dramatically advised Nixon, “for what happens in Chile over the next six to twelve months will have ramifications that will go far beyond just US-Chilean relations.”

Document 2.7

NSC, Telcon, Kissinger Discussion with Nixon on the coup in Chile, September 16, 1973

Sep 16, 1973

Source

DNSA.

In their first substantive conversation following the military coup in Chile, Kissinger and Nixon discuss the U.S. role in the overthrow of Allende, and the adverse reaction in the news media. When Nixon asks if the U.S. “hand” will show in the coup, Kissinger admits “we helped them” and that “[deleted reference] created conditions as great as possible.” The two commiserate over what Kissinger calls the “bleating” liberal press. In the Eisenhower period, he states, “we would be heroes.” Nixon assures him that the people will appreciate what they did: “let me say they aren’t going to buy this crap from the liberals on this one.”

Document 2.8

Jun 8, 1976

Source

National Security Archive U.S.-Chile Relations collection

In Santiago for an Organization of American States (OAS) meeting, Kissinger meets privately with General Pinochet. Despite being briefed by his aides that the regime’s rampant human rights violations have made Chile “a symbol of rightwing tyranny” and advised to press Pinochet on that issue, Kissinger takes a decidedly solicitous approach. “My evaluation is that you are a victim of all left-wing groups around the world and that your greatest sin was that you overthrew a government which was going communist,” he tells Pinochet, avoiding any pressure on human rights or a return to civilian rule. “We want to help, not undermine you.“

Document 2.9

Jun 16, 1976

Source

DNSA.

Following his visit to Chile and his meeting with Pinochet, Kissinger read an article in the Washington Post reporting on remarks made by Robert White, a member of the State Department delegation to the OAS conference (and later U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador). White criticized the Pinochet regime for rejecting the OAS report on ongoing human rights abuses in Chile. Unbeknownst to White, only a few days earlier, Kissinger privately told Pinochet that ”we want to help, not undermine you.” Now, Kissinger is angry that a U.S. official has publicly challenged Pinochet on his human rights record. ”This is not an institution that is going to humiliate the Chileans,” he states. ”It is a bloody outrage.” Kissinger tells Rogers, the State Department’s top official for Latin America, that they should fire White.

III. KISSINGER AND HUMAN RIGHTS

Secretary Kissinger’s abject embrace of the Pinochet regime, and disregard for its repression, contributed to a broad public and political movement to institutionalize human rights as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. As Congress began passing laws restricting U.S. assistance to regimes that violated human rights, Kissinger’s distain for the human rights issue escalated. His willingness to endorse, support and accept mass bloodshed, torture and disappearance by allied, anti-Communist military regimes, is reflected in various declassified documents.

Document 3.1

Jun 30, 1976

Source

DNSA.

In this brief conversation, Henry Kissinger berates his aide after learning that the State Department’s Latin America bureau has issued a demarche to the Argentine military junta for escalating death squad operations, disappearances and reports of torture following the coup in March 1976. The demarche was recommended by Ambassador Robert Hill and conveyed by him to Foreign Minister Guzzetti on May 27. A similar message was given to the Argentine ambassador in Washington, D.C., by one of Shlaudeman’s deputies, Hewson Ryan. But the demarche appears to contradict a message that Kissinger had personally given to Guzzetti during a private meeting in Santiago on June 10; to act ”as quickly as possible” to repress leftist forces in Argentina. Now Kissinger demands to know ”in what way is it [the demarche] compatible with my policy.” He tells Shlaudeman: ”I want to know who did this and consider having him transferred.”

Document 3.2

Oct 7, 1976

Source

Freedom of Information Act request by the National Security Archive, released November 2003.

As a follow up to a meeting they held in Santiago in June, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Argentine Foreign Minister César Guzzetti meet again at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City and discuss the Argentine military regime’s repressive campaign to eradicate the left. Kissinger offers U.S. support: “Look, our basic attitude is that we would like you to succeed. I have an old-fashioned view that friends ought to be supported. What is not understood in the United States is that you have a civil war. We read about human rights problems but not the context. The quicker you succeed the better.”

Document 3.3

Oct 19, 1976

Source

U.S. State Department, Argentina Declassification Project (1975-1984), August 20, 2002. Transcription

U.S. Ambassador Robert Hill sends this protest to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that he has emboldened the Argentine military by not giving Foreign Minister Guzzetti a strong disapproval from Washington for their human rights violations. ”Guzzetti’s remarks both to me and to the Argentine press since his return are not those of a man who has been impressed with the gravity of the human rights problem as seen from the U.S.” Ambassador Hill reports. “Both personally and in press accounts of his trip Guzzetti’s reaction indicates little reason for concern over the human rights issue. Guzzetti went to US fully expecting to hear some strong, firm, direct warning of his govt’s human rights practices. Rather than that, he has returned in a state of jubilation. Convinced that there is no real problem with the USG over this issue.” Hill concludes that “While that conviction lasts it will be unrealistic and unbelievable for this embassy to press representations to the GOA over human rights violations.”

IV. KISSINGER AND OPERATION CONDOR

Kissinger’s resistance to pressing the Southern Cone military regimes on human rights extended to their international assassination operations known as Operation Condor. In early August 1976, Kissinger was briefed by his deputy on plans, under Condor, “to find and kill terrorists … in their own countries and in Europe.” His aides convinced him to authorize a demarche that would be delivered to General Pinochet in Chile, General Videla in Argentina, and junta officers in Uruguay—the three Condor states most involved in transnational murder operations. But when the U.S. ambassadors to Chile and Uruguay raised objections to delivering the demarche, Kissinger simply rescinded it, ordering that “no further action be taken on this matter.”

Five days later, Condor’s boldest and most infamous terrorist attack took place in downtown Washington, D.C., when a car bomb planted by Pinochet’s agents killed former Chilean ambassador Orlando Letelier and his young colleague, Ronni Moffitt.

https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/cold-war-henry-kissinger/2023-05-25

Ähnliche Beiträge

Im Solde des Henry Kissinger: der Massen Mörder Videla, wurde in Argentinien abgeurteilt

Dezember 23, 2010

In „Geo Politik“

Die Morde des Henry Kissinger in Chile, wo er den gewählten Präsidenten Salvador Allende ermorden liess

April 30, 2016

In „Chile“

Partnerin im Kinder Schänden: die neue Argentinische Aussenministerin Susana Malcorra und der „Schleichender Staatstreich“ in Argentinien

Januar 7, 2016

Neueste Kommentare